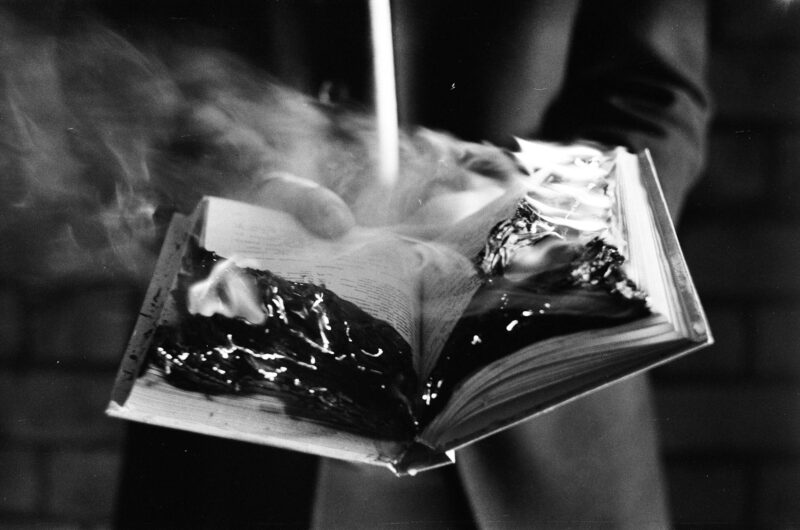

An “exquisite irony” that happened to Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 upon its first publication in 1953 was that edited, censored versions of it (with drugs and profanity removed) began circulating the markets. This was without Bradbury’s knowledge, until 1979 when some teachers and students noticed the difference in their classroom copies, and it reached Bradbury’s ear. The text was restored, and so all the copies we hold at this point in time are the original text: a dystopia about censoring and burning of books.

Bradbury warns against censorship—a kind of airbrushing of pores—just as Faber does in the book. “Do you see why books are hated and feared? They show the pores in the face of life. The comfortable people want only wax moon faces, poreless, hairless, expressionless.” There’s a growing tendency to only write inclusive, representative, safe literature—since books have become more and more sensitive, increasingly afraid of stepping on toes, so instead of challenging and pushing boundaries as they are meant to, they’ve taken to staying rooted in one place like a timid child. In doing so we cut out more and more literature from curriculums, dismiss more texts as irrelevant, and in doing so we lose something.

We’ve been discussing this in fiction class where we’re currently reading Philip Roth. Now Roth was an interesting figure—a messy personal life, and then wrote it into an autobiographical series in which the protagonist was quite literally named Philip Roth. But his prose is beautiful. In fact, I think it is one of the wittiest, snarkiest portrayals of American life that I have ever seen. And he was a Jew accused of being anti-Semitist. He wasn’t afraid to step on any toes. That’s what our professor said—to be unafraid of giving offense. For when you are offended, you feel things and you begin to think, and then often to act. (And it really was jarring to see, in one of the essays on Fahrenheit, to see the picture of the Danish edition cover: 233° Celsius. It really does alter the character of the book. Apparently, Bradbury soon had the original Fahrenheit title restored for foreign editions.)

After re-reading this dystopia after many years, I understand it as a defense of books more than anything else. It’s an attempt to stake out a space for literature, like a worried protective father trying his best to build a shelter for his children in the coming years in a world that seeks to harm them. As I was reading this book at work, my supervisor walked past and remarked that it was a “terrifying” book in 2025, and I understood what she meant as the happenings around the world of the last month have been momentous ones, and in this midpoint of a year where we are no farther from 2050 than from 2000, we have backed our already-threatened literature into a further corner.

Flipping to the end of this edition of the book, you will find yourself greeted with a rallied troop of writers such as Neil Gaiman, Margaret Atwood, Orville Prescott, and Nelson Algren. In their essays and reviews of the dystopia, you feel like you are listening in on a meeting of concerned army generals in war. Strangely this evokes an image of steady pillars rooted in a shaky foundation. Think about it this way: we are standing at a brink of a cliff, gazing down into a fuming valley, but along the edge are concerned onlookers, like these writer-minds of our time, who will do something—fight for solutions—rather than give up and drop off the edge. As the heat from the valley intensifies, threatening to melt the cliffs, when you look around you, the line of fellow onlookers positioned along the cliffs also stretches long and far.