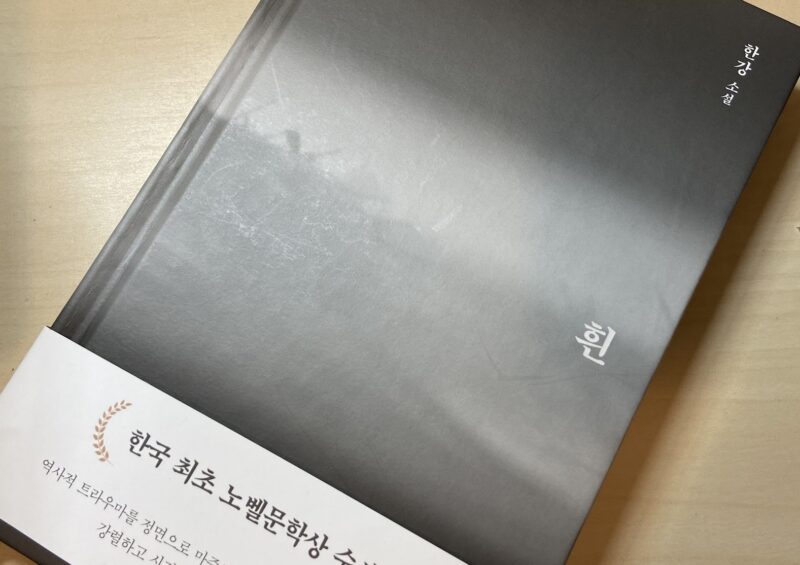

I’ve never before written a review on a book that I read in another language, so this is a first. The White Book by Han Kang, Nobel Prize-winning author, is 흰 (simply “white”) in Korean, the language it was written. It is a series of vignettes and meditations on objects that are white, each one like a pearl the narrator offers to readers, gleaming and unexpectedly beautiful, with the mute unspeakable theme of grief.

A door

The mist

A cloth

A white city

As we’re handed each object to examine, the author (or the narrator—we find out later that these two are one and the same) reveals how each object functions as a portal to another hatch, another level, another realm that she wanted to be transported to in the first place.

A door—to the apartment she lived in during her time in Warsaw, Poland. It’s chipped, cracked, once-white but now dirty, with the number 301 that someone carved with a jackknife. She—our narrator—comes armed with a bucket of white paint, and a roller. She paints over the door with new whiteness. Later she steps outside into the vicious cold of night. It is December in Warsaw, snowflakes drifting like feathers over her, her paint bucket, and the lamppost.

The mist—that is, the morning mist in Warsaw—a great movement of water, rippling like a beast at the boundary between our world and the world beyond, according to our narrator.

A cloth—in which the narrator’s older sister, birthed perilously at home one winter, was wrapped carefully, nursed by the trembling young mother—only twenty-three herself—but died within two hours. And the young father wraps it in more white cloth, and walks slowly up the winter mountain to bury it.

A white city—Warsaw, Poland itself. Bombed in the 1944 Uprising, a site of white ashy debris in a black-and-white museum documentary. But from that whitely decimated state, our narrator marvels, it reconstructed itself.

I still don’t quite understand how Han Kang pulls off this structure, where everything in the novel happens within this white liminal space, a blank-white studio in a dream: no walls, ceiling, or dimension.

But if I described these vignettes earlier as pearls, they’re also like candy. Though each one is haunting and devastating, the essays also gleam with originality, making you want to taste the next. And these firm little pearls, or candies, are interconnected—not linearly, like a necklace, but with a connection here, a recurrence there, that end up creating a great white web. We meet the dead sister again, over different times and places, from different angles, and alternate universes. The capital of Poland, annihilated by war, we also meet again in present-day, restored, as well as images of old rubble through digital film footage from the forties. In the afterword, Kang says, simply: her lost sister is Warsaw. Or at least, they are two entities that share a fate. Once dead, yet insistently existing in her life still.

How beautiful that she can meet, through imagination, an older sister she never really saw, and liken the quiet streets of Warsaw to her presence. Within The White Book is a whole universe built on objects that are white, gesturing to a myriad other colors, cities, and persons missed.